Compatibility of Cosmetic Products – an Intensive Testing Strategy

Interview with Ilka Pusch – Customer Service Consultant, Katharina Nickel – Customer Service Consultant and Dr Dörte Segger – Lab & Customer Service Manager at

SGS Institut Fresenius GmbH

Worldwide, approximately 60-70% of women and 50-60% of men rate their skin as sensitive.1 As a result, the demand for cosmetic products specifically for sensitive skin is rising, and manufacturers are producing more products in this category to meet market needs. However, various studies have shown that skin-irritating and allergy-triggering ingredients, such as critical preservatives or critical essential oils, can be found in some of these cosmetic products.2 Therefore, the EU is constantly working on expanding the Cosmetics Regulation to include substances that must be labeled in the future. Another approach to ensuring the compatibility of cosmetic products is a comprehensive and extensive testing strategy that can identify as many potential incompatibilities as possible.

What is the definition of sensitive skin, and how can intolerances be triggered?

Clinically, sensitive skin is mainly defined in purely sensory terms as short-term feelings of tightness, stinging, burning, tingling, pain, and/or itching. Visible erythema rarely occurs.3-6 Classification is made either by a skin sensitivity questionnaire or by using the atopy criteria since skin sensitivity correlates with atopy.7,8

Intolerances, such as eczema, can be triggered by genetic dispositions, penetration of pathogenic microorganisms, environmental (pollution), or a disturbance of the skin barrier, for example, by surfactants.9 Surfactants can dissolve lipids out of the epidermis. Due to the lack of lipids, the skin barrier becomes leaky, water can evaporate faster, dirt and/or germs can penetrate quicker and deeper, therefore dryness or eczema would be triggered.

How can cosmetic products be formulated tolerable?

Firstly, it depends on the ingredients and concentrations in the products. For this purpose, the EU has listed all permitted substances and their maximum concentrations in Regulation EC No. 1223/2009, which is regularly updated by annexes. The declaration of ingredients (INCI) on the products is mandatory in the EU. However, companies often label allergenic ingredients like fragrances only under the general term "perfume" and without the individual ingredients. Furthermore, it is misleading when companies consolidate their products with claims such as "hypoallergenic," "allergy-free," or "sensitive". For example, "hypoallergenic" only states that the cosmetic product tends to cause fewer allergic reactions than a comparably formulated product, and it does not contain any known allergens, precursors of allergens, or substances without relevant data on their sensitizing potential. It says nothing about the total prevention of an allergic reaction (Annex IV). So, in 1998 the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS) judged the claim "hypoallergenic" to be deceptive because it can be assumed that the cosmetic product is particularly safe and well tolerated and does not trigger allergies (SCCS/1567/15). Interestingly, even the statement "allergy-free" is prohibited according to Annex III of the technical document. For consumer protection and stopping the rise of allergies, transparent formulations and the avoidance of generic claims are essential.

In addition to ingredients and claims, the regulation also specifies how the safety of a cosmetic product must be evaluated. Accordingly, new products do not have to be tested if safety data, such as a toxicological profile or similarly formulated products, are already available. In that case, an evaluation of existing data is sufficient. However, this is a theoretical consideration that does not consider cross- reactions, so we strongly recommend an in vivo evaluation of new formulations.10

What reactions can occur with an intolerance?

A distinction is made between immediate reactions, long-term responses, and allergies. Immediate reactions are usually visible by redness, edema, or sensory tingling, burning, a feeling of heat, and itching. The reactions usually disappear after 30 min to 3 h.

Intolerance after long-term use is mainly shown by redness, pustules, papules, scaling, and/or itching and burning. These reactions usually last for several days.

Allergies are shown by redness, edema, and/or sensory discomfort, which in individual cases can manifest into eczema. Once the body has developed an allergy, it is very difficult or impossible to reverse.

What are strategies for testing cosmetic products for very good compatibility or for identifying very well-tolerated formulations?

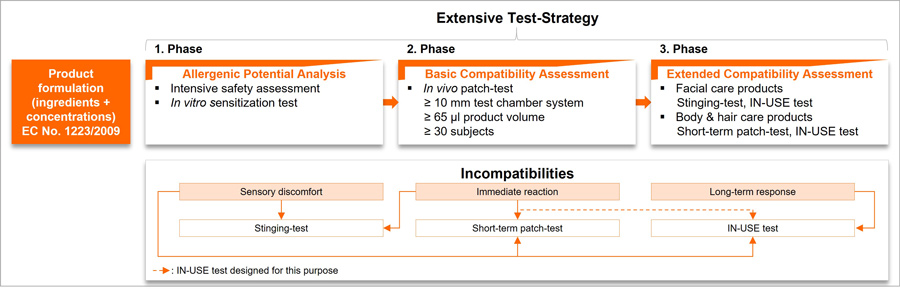

To identify and evaluate as many potential incompatibilities as possible, we recommend the following test strategy, which consists of three different phases:

The first phase, "Allergenic Potential Analysis," consists of an intensive safety assessment and an in vitro sensitization test (SENS-IS test). The safety assessment examines the product formulation for its allergenic potential. The product formulation must be free of known allergens, precursors of allergens, and substances without relevant data on sensitization potential. In the SENS-IS test, the gene expression of relevant biomarkers (gene sets for irritation and sensitization) is analyzed using a reconstructed human epidermis.

For fundamental compatibility assessment in vivo, in the second phase, patch tests are used, where the cosmetic product is applied under a special patch to mimic intensive biological exposure.11 It is important to apply enough product volume, select a suitable number of subjects, and adapt the type of exposure to the product type. Therefore, we recommend performing the patch tests with at least a 10 mm test chamber system, 65 µL product, and on 30 subjects, as studies have shown that when using smaller test chamber systems (8 mm, up to 20 µL product) sometimes no reactions occur at all. In test chamber systems with a diameter of 10 mm or larger, significantly more and stronger reactions occur.12-14

To evaluate the compatibility also under real application situations, we recommend performing an extended compatibility assessment in the third phase. For testing facial care products, we suggest stinging, IN-USE, and/or short-term patch test, and for body and hair care products an IN-USE and short-term patch test.

Further, we purpose recording sensory discomfort and immediate reactions by a short-term patch test with a larger volume of product and short application time as well as by stinging test according to Frosch and Klingmann.15

For the analysis of long-term aspects, we recommend an IN-USE application over at least two weeks with at least 30 subjects. An IN-USE test, which also takes tolerance aspects into account, is suitable for the detection of sensory discomfort, long-term responses, and immediate reactions.

Literature

- Farage MA. The Prevalence of Sensitive Skin. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019 May 17;6:98.

- Rick JW, Brannon M, De DR, Shih T, Hsiao JL, Shi VY. Allergen Composition, Marketing Claims, and Affordability of Pediatric Sunscreens. Dermatitis. 2022;33(6):435-441.

- Ständer S, Schneider SW, Weishaupt C, Luger TA, Misery L. Putative neuronal mechanisms of sensitive skin. Exp Dermatol. 2009 May;18(5):417-23.

- Farage MA, Maibach HI. Sensitive skin: closing in on a physiological cause. Contact Dermatitis. 2010 Mar;62(3):137-49.

- Misery L. Sensitive skin. Expert Review of Dermatology. 2013;8(6): 631-637.

- Misery L, Loser K, Ständer S. Sensitive skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:2-8.

- Diepgen TL, Fartasch M, Hornstein OP. Evaluation and relevance of atopic basic and minor features in patients with atopic dermatitis and in the general population. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1989;144:50-54.

- Diepgen TL, Fartasch, M., Hornstein, OP. Kriterien zur Beurteilung der atopischen Hautdiathese. 1991.

- Yang G, Seok JK, Kang HC, Cho YY, Lee HS, Lee JY. Skin Barrier Abnormalities and Immune Dysfunction in Atopic Dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Apr 20;21(8):2867.

- Rodriguez O, Brod BA, James WD. Impact of trends in new and emerging contact allergens. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2022;8(1):e006. Published 2022 Mar 25.

- Frosch PJ, Kligman AM. The chamber-scarification test for irritancy. Contact Dermatitis. 1976 Dec;2(6):314-24.

- Hannuksela A, Hannuksela M. Irritant effects of a detergent in wash, chamber and repeated open application tests. Contact Dermatitis. 1996 Feb;34(2):134-7.

- Brasch J, Szliska C, Grabbe J. More positive patch test reactions with larger test chambers? Results from a study group of theGerman Contact Dermatitis Research Group (DKG). Contact Dermatitis. 1997 Sep;37(3):118-20.

- Löffler H, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Effendy I, Maibach HI. Pitfalls of irritant patch testing using different test chamber sizes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001 Mar;12(1):28-32.

- Frosch PJ and Kligman AM. A method of app raising the stinging capacity of topically applied substances. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 1977; 28:197–209.